Our class at the Chippendale International School of Furniture recently visited the Woodcote House in Midlothian, Scotland. This was only one of several “field trips” that the class went on and was a wonderful and extremely valuable experience for me. I’m not a furniture designer, nor do I play one on TV, but I have designed (to some extent) all of the pieces I’ve made so far and am making now. The most interesting part of this though is that I’ve never really been attracted to the Mid Century Modern style, so it was a thoroughly pleasant and welcomed surprise for me to find that this visit was the most interesting and valuable to me of all of our field trips.

***Note*** That does not mean the other field trips were not each valuable. I found each of these visits to be eye-opening and wonderful with the up close and personal access to old and absolutely breathtaking pieces of furniture and art with the stories and history behind them.

Eleanor Morris of Woodcote, PhD, PCRTPI Scotland was our very gracious hostess and an invaluable wealth of knowledge of the furniture there. She gave us the history of each piece and its significance to Scotland, with some great personal stories behind many of them. Unfortunately, I do not have a great (or even good) memory and can’t remember even one of those stories…but they were great!

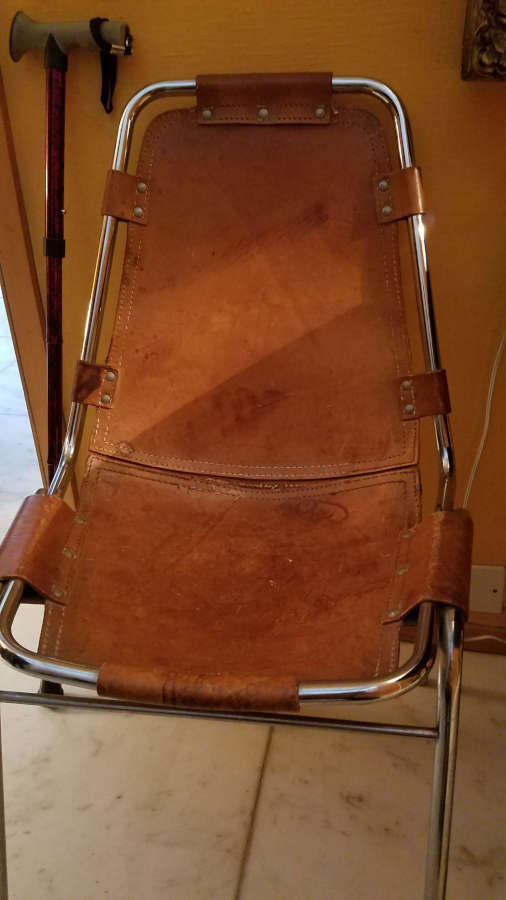

Probably the most iconic piece we saw was the Le Corbusier Chaise Longue a Reglage or the LC4 or, I think, the B306, which sounds like a military bomber jet.

An early version of this had taller back legs. This one has a calfskin seat with chrome tubing and rubber guides so the seat frame doesn’t slip and slide while you are trying to sit down. It was designed by Le Corbusier, with Pierre Jeanneret and Charlotte Perriand. It has been in production since the 1930s, first made by Thonet and since the 1930s by Cassina.

There were also a pair of LC3 Grand Confort “Cushion Baskets” from about the same time in calfskin.

I sat in one of these for a bit, and even after 54 plus years (at least as old as I am) they are still very comfortable.

Next are some pieces by Mies van der Rohe. The Barcelona chairs and divan.

The couch was designed for a New York architect in the 1930s and became famous when it was shown in the Glass House, which was completed in 1949 in New Canaan, Connecticut.

Knoll took over production in 1964 and it wasn’t until 1987 that the divan was called the Barcelona (like the chair) because of its resemblance to the chair.

The Les Arcs resort chair, by Charlotte Perriand (or Italian designer DalVera). I’ve seen some pictures of these with black steel tubing. They were designed for the Les Arcs ski resort in Savoie, France.

The Tulip table and chairs by Eero Saarinen were the first pieces we saw when we entered the house. The chairs were surprisingly comfortable and sturdy, even for a heavier person as myself. The table caused a bit of a stir when it came to Scotland. Seems that for safety reasons it was supposed to have two bases. Even with a half dozen of us sitting at the table, it was never tippy or unstable.

Marcel Bruer was influenced by the De Stijl movement while an apprentice at the Bauhaus and drew on the bicycle frame as inspiration for the Wassily chair in 1925.

Several of the other students sat in these chairs and said they were quite comfortable.

There were quite a few other very memorable pieces at the house, but they will have to wait for another post.