One of the most valuable things I’ve gained from being a student at the Chippendale International School of Furniture is access to antique, and even ancient, furniture that I’d only ever seen in books and online. We have visited homes and museums and have enjoyed access to furniture that I didn’t know existed. We have also had access outside of school to auctions and antique shops where I’ve fondled and caressed (not in a creepy way) beautiful antiques and vintage pieces of furniture for much longer than was appropriate.

Late 18th C. George III Style ‘Chinese Chippendale’ Mahogany Urn Stand

I’ve been taught since I was young that when at any museum, or in the vicinity of delicate antiques, you ‘look but don’t touch‘ , so it’s been an amazing treat to be able to visit museums and homes and have that extra bit of access where you can touch the pieces, pick them up, turn them over and look at the underbelly because, in order to really understand how furniture was made, you have to look under, inside, and behind that piece. I first learned this from a blog, Pegs and Tails, that I’ve been following for a few years, and also from Peter Follansbee’s blog but since starting my furniture class I’ve had a chance to experience this first hand.

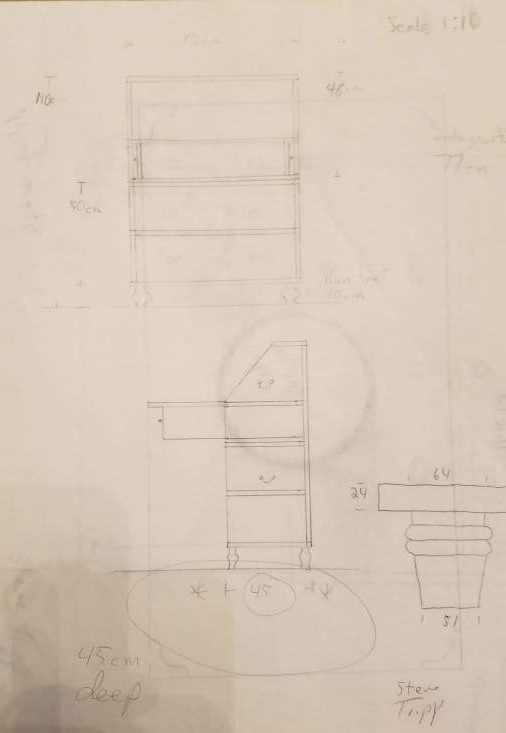

I’ve been able to see and help work on some wonderful pieces of furniture that have come in the School since I began my classes. From damaged chairs to cabinets, desks, dressers, and tables, they have all fascinated and intrigued me, but one particular moment that stands out to me is when a late 18th C. (around 1780) Italian table came in for repair/restoration. I’d not seen a piece like this before, but was immediately drawn to it because as soon as I started looking closely I could see so many wonderful and intriguing things about it.

But the one thing that caught my eye was when I saw some holes in the veneer and marquetry that didn’t look like normal wear and tear.

I knew that I remembered seeing this somewhere, so I went back to some blogs I follow and found it in the Pegs and Tails blog in a post called “A Thorny Subject” dated 15 Jan 2012. He talks about veneer pins, which were used in period veneer work. They were made of thin sheet steel and guillotined or sheared with a taper. The edges were sharp enough to cut fingers so they were made to cut through the veneer instead of wedging into it. I’ve not found any sheered veneer pins for sale today (only round), but it may just be that my Google-Fu skills are rusty.

Per the article, the veneer pins were often used on uncooperative veneer in corners, on either side of a split or joint, or anywhere the veneer refused to cooperate.

This was one of those ‘Eureka’ moments for me and just drove home the fact that I’m intrigued by the methods and tools used by pre-industrial furniture makers and crafts people. I was fairly bouncing around the table, babbling like an idiot about these pin holes because it tied together things I’d read about to things I was able to experience. And quite often, making it real is the catalyst for education.